From Cloister to Warner House: Building and Preserving Architectural Legacy

American Architecture and Urbanism// Yale University

Whether a student or a visitor of Yale University, you are bound to make it outside of the main campus and stumble upon Hillhouse Avenue, described by both Charles Dickens and Mark Twain as “the most beautiful street in America.” Barely two blocks long and housing an array of homes all seemingly built in different architectural styles, it is a true testament to Yale’s rich history and architectural heritage, even forming the Hillhouse Avenue Historic District.

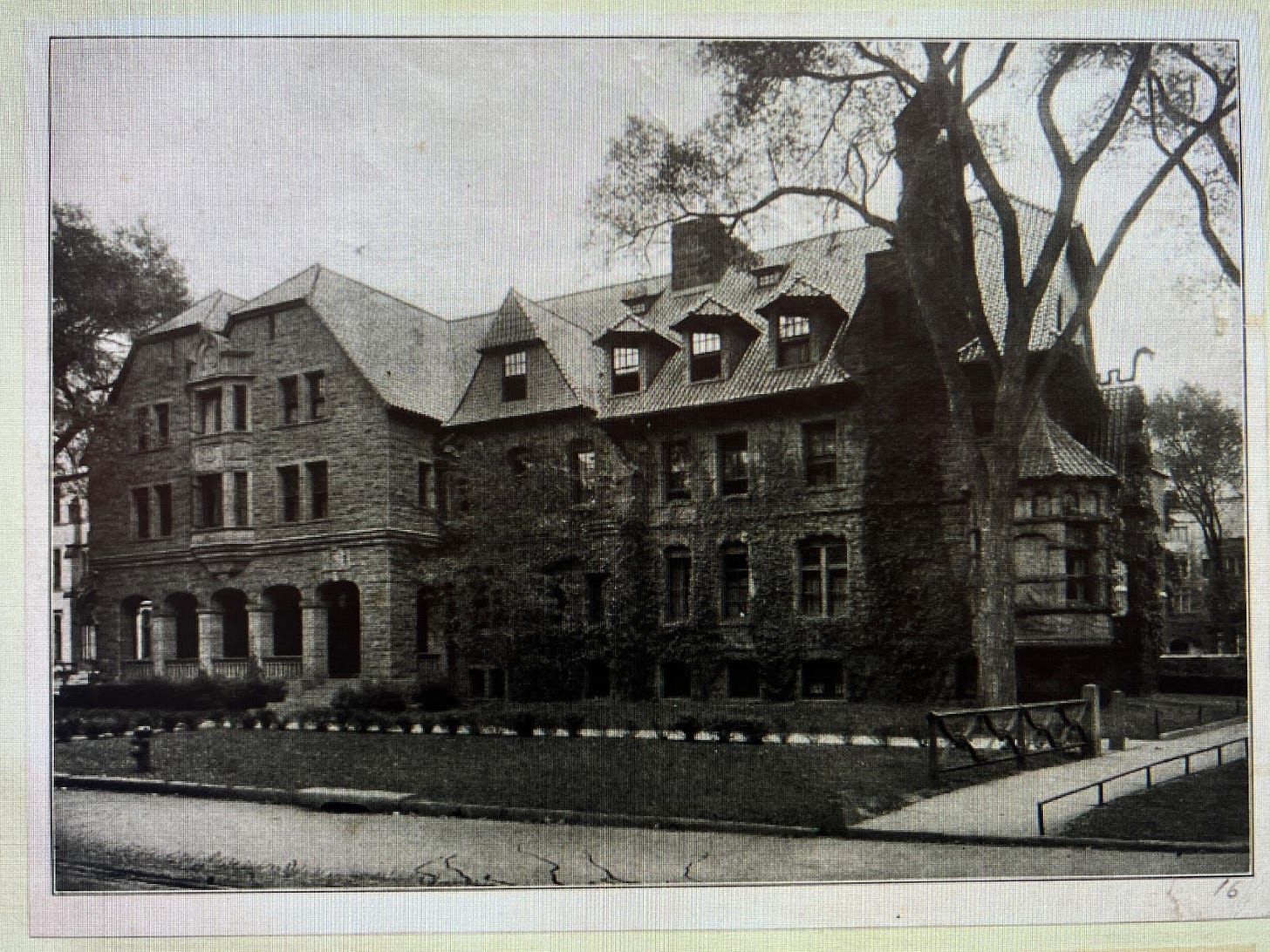

At its lower Eastern corner, right at the intersection of Hillhouse Avenue and Grove Street, one can see what looks to be a brownstone home, important looking people walking in and out as students passing by without a second thought which may be odd due to the building's importance. The main plaque out front, its blue color contrasting the brownstone of the building, reads “Warner Hall,” and the building is a stunning example of Tudor Revival architecture, with a brownstone facade, half-timbering, brickwork, and also features a floating corner addition. And despite this extravagance, it nearly shrinks in comparison to the adjacent and overarching St. Mary’s church, the large temple like Kirtland Hall across the way on the Western corner of the intersection, and Silliman college on the other side of Grove Street.

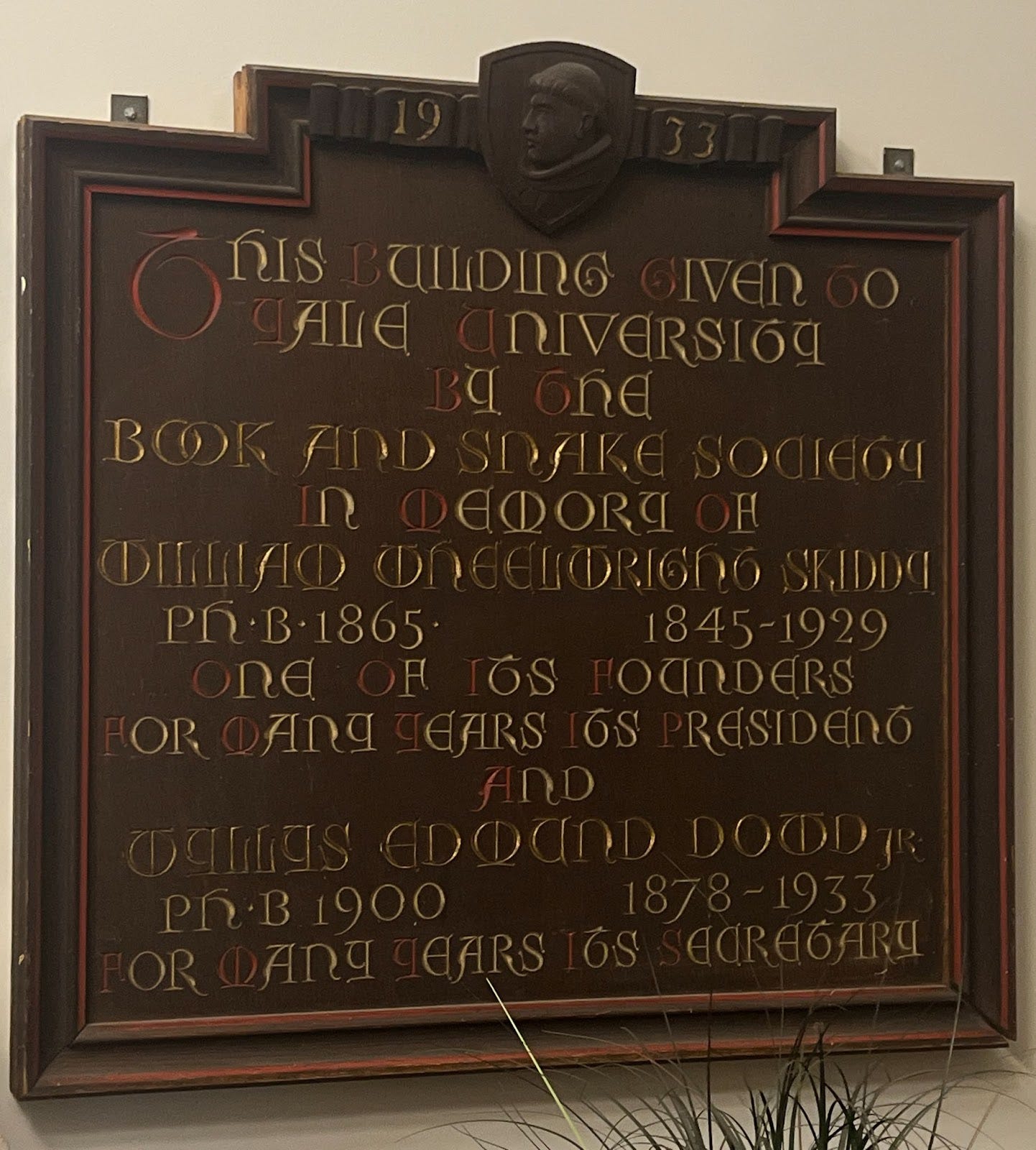

And despite its quiet nature, Warner House presents a deep history that begs to be told, as indicated by the plaques that hang in its first floor lobby and haunt me whenever I enter to begin my work shift as the Dean’s Student Aide; thankfully, the opportunity presented itself the moment this study was assigned. Better known as the Cloister and dating back to the late 19th century, the building was originally a residence hall for the Book and Snake society, one of the oldest secret societies on Yale’s campus. Today, the Warner House is used for administrative offices, including the Yale College Dean’s Office.

Physical Description:

Warner House presents a Tudor Revival style, showcasing a distinctive brownstone facade with half-timbering, brickwork, and stone details. The corner exposed to the intersection includes an octagonal floating corner addition, an element chosen with the intention to create more interior space and add greater visual interest to the exterior, especially given its steeply pitched roof and bay windows. The corner addition is situated by a porch on the Grove Street Side, which used to be the original entrance when the building was still used as a dormitory but is now actually barricaded from the inside conference room. The main entrance is now located on Hillhouse Avenue, located on the other side of the corner addition and in the center of the front facade, fitted with a stone archway with carved motifs and a coat of arms.

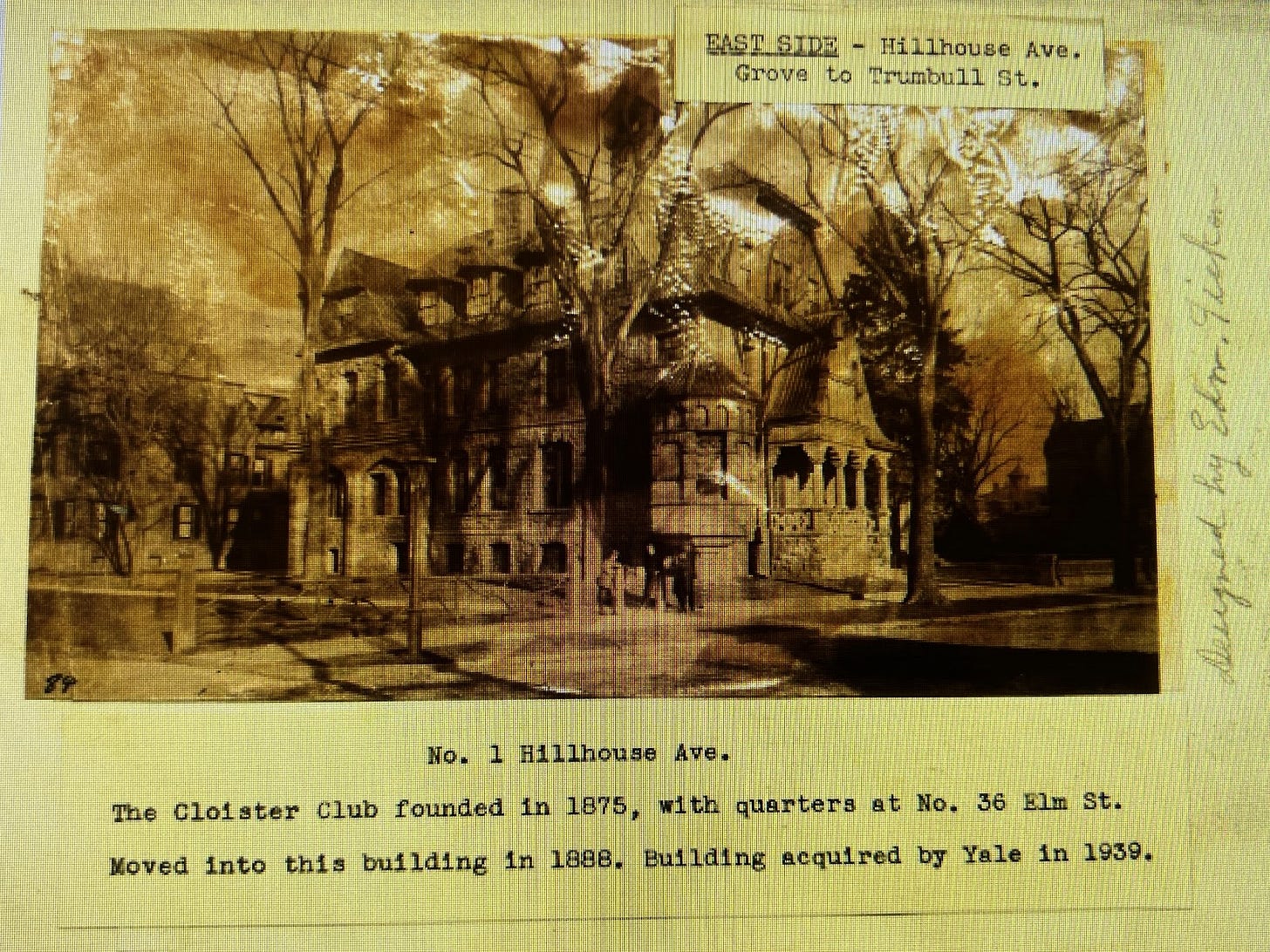

The first map showcasing the building was published in the Atlas of the city of New Haven Connecticut 1888, and illustrated a rectangular building for the “Sigma Delta Chi Society of Yale College.” The primary way to track the evolution of the building, however, is through the Sanborn Insurance Company Maps, the first one including “The Cloister Club” being the one from 1901. It clearly illustrates a stone building, nearly rectangular as it now included illustration of the entrance features, and the building's steeply pitched roof, with its multiple gables and dormer windows. The 1911 Sanborn map shows the same illustration, yet “The Cloister” has now been relabeled as the “Stone Trust Association,” which emphasizes the interweaving nature of the many identities of the society as these labels will continue to change in subsequent maps to indicate the same tenant. In the 1923 map, however, an extension to the building has been made, extending it further into the street on the Hillhouse side as it presents a ramp to increase accessibility but also allow for most rooms to be built above it. The building now looks like two connected rectangular shapes joined in a T-Shape. The roof of the building is varied in its design, mostly half-hipped but at times also gabled above windows, covered with slate tiles and showcasing many decorative finials and chimneys. The stone strapwork above the original entry porch has additionally been identified to “signify student solidarity and Brüderschaft by architectural reference to medieval German university life.”

The interior of the building has many original features, such as wood paneling, fireplaces, plaster moldings, and hardwood floors. An interesting and notable feature, which is actually quite difficult to see from the street due to being covered by foliage and its intentional clear design, is a glass floating connector bridge which connects Warner House with Dow Hall. The only time it is visible on a map is through the use of Google Maps.

Streetscape and Urban Setting:

The broader urban context and the interrelationship of Warner House and its surroundings proves for a very interesting study. Hillhouse Avenue, originally laid out in 1792, is a two-block long street that runs from Grove Street to Sachem Street. Privately owned until 1862, it housed the family mansion of its namesake James Hillhouse, on the hilltop at the end of the avenue. When the plot was partaken in 1942, numerous houses began to be built along the street in various styles, encompassing New Haven’s best-preserved array of high-style 19th- and early 20th-century suburban villa architecture, most examples of nationally and locally renowned architects. Because of the nature of the street, its lots, and its orientation to the nine-square-grid of New Haven, Hillhouse Avenue can even be considered to be the first suburb in the United States.

The street itself showcases two rows of meticulously planted Elm trees which account for its parklike character, allowing for a dignified procession up to Sachem’s wood. Interestingly, multiple maps attached below show the New Haven Northampton Railroad cutting straight through the first section of Hillhouse; it can be assumed that this has today become the campus’s beloved bike path and walkway. Although railroads have been identified to be bearers of economic prosperity and social change, it begs the question why allow the railroad to cut through the beautiful plot of land, especially as early as 1874, way before the demolition of the Hillhouse mansion. Yale now owns all of the properties on Hillhouse Avenue except for St. Mary's Church and its parish house, yet regardless of the changes that took place, the street retains its verdant character as it is listed and protected as the Hillhouse Avenue Historic District.

Warner house was built in 1898 as a residence hall for the Book and Snake society, and was itself dubbed “one of the most picturesque buildings on the Yale campus.” Located on the lower block of Hillhouse Avenue, near the center of Yale’s campus, it is surrounded by other historic buildings that reflect Yale’s history and culture, such as St. Mary’s Church, Woolsey Hall, the Grove Street Cemetery, and Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall. Since 1933, the building has been used for administrative offices, and having been the seat of both the provost and dean of the University, Warner House is a place of significant importance to the students and community members, often acting as a place of protest. For instance, in April of 2015 the Graduate Employees and Students Organization took to the steps of Warner House to address gender and racial inequities at the graduate school, and the following month roughly 300 GESO members and supporters marched from the end of Hillhouse Avenue to the Provost’s Office to present their petitions.

Nevertheless, the building’s streetscape and urban setting contribute to its architectural significance and historical value. It is a landmark of Yale’s rich history and the university’s relationship with New Haven.

Social History

The building served as a residence hall for the Book and Snake society until 1933, when Yale’s residential college system was established. The society then moved to its current location on College Street, and sold the Cloister to Yale University, who used it for various purposes, such as housing for graduate students and faculty, offices for academic departments, and classrooms. Additionally, it was renamed after Hiram Bingham Warner, a Yale alumnus and benefactor of the society, who donated money for its heavy renovations. It soon became the office of the Provost, who serves as the chief academic officer of the university. The Provost’s Office remained in the Warner House until 2002 when Provost Benjamine Polak announced its move to 2 Whitney Avenue. This was done in order for the building to house the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, responsible for overseeing the education and research of graduate students, as well as the offices of the Dean of the Graduate School, the Academic Deans, Admissions, Financial Aid, the Office for Graduate Student Development and Diversity (OGSDD), and the Teaching Fellow Program. The Provost would move back into Warner House in the future, but not for long as it will be replaced with the Yale College Dean’s Office soon enough. In its contemporary use, although it is no longer a student dormitory, the building functions as a house for the larger Yale faculty, regularly hosting various events and activities, such as receptions, lectures, workshops, and celebrations to bring the various parts of the university staff together and bridge communication.

A prominent corner site, Warner House is a significant part of Yale’s history and culture, as it reflects the changes and continuities that have shaped the university over more than a century. It is a place where academic excellence, intellectual diversity, and social responsibility are fostered and celebrated.

Site History

For some reason, one of the most interesting parts of the building has always been imagining its previous use as a society, housing its members and also acting as their meeting house. The Book and Snake society, also called the Sigma Delta Chi Society, was established by students at the Sheffield Scientific School on November 17, 1863, essentially a three-year society. It was first housed on the top floor of a building on College and Chapel Streets and then the top floor of 953 Chapel Street. In 1876, however, the society constituted itself as the Stone Trust Corporation so that it could own property and hold money, and this name honored Lewis Bridge Stone, an early member of the Society. With this access to funds, the Book and Snake Society built Cloister Hall in 1888, which served combined functions as both a chapter house and dormitory. Soon, several Yale graduates were hired by Sheffield's fraternities to design “tombs” and fraternity houses. Book and Snake built a tomb that functioned as a meeting hall in 1901, accessible only to members and alumni, at the corner of Grove Street and High Street in New Haven, designed in Greek Ionic style by Louis R. Metcalfe. However, it was only when Yale started its residential college system in 1933 that the Book and Snake Society sold Cloister Hall to the University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“A Classic Street Ages, but Retains Its Beautiful Bones.” Hartford Courant, Hartford Courant, 12 Dec. 2018, www.courant.com/2015/01/24/a-classic-street-ages-but-retains-its-beautiful-bones/.

Carroll, Richard C. “Hillhouse Avenue Buildings .” Buildings and Grounds of Yale University, Yale University, New Haven, 1979, p. 50. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=yale_history_pubs

Dana Collection: Dana, Arnold Guyot, 1862-1947. New Haven old and new. Collection Nbr 32 and 33, New Haven Museum

Finnegan Schick “Geso Presents Grievances to Warner House.” Yale Daily News, 23 Apr. 2015, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2015/04/23/geso-presents-grievances-to-warner-house/

Finnegan Schick. “Geso Stages Protest in Front of Warner House.” Yale Daily News, 6 May 2015, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2015/05/05/geso-stages-protest-in-front-of-warner-house

“The Graduate School Moved to Warner House.” The Graduate School Moved to Warner House | Yale Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, 2 July 2015, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjzjsuOh-OBAxUpGVkFHRHFDM4QFnoECBQQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fgsas.yale.edu%2Fnews%2Fgraduate-school-moved-warner-house&usg=AOvVaw21qI0EcP-4A9RX3R4hgWjf&opi=89978449

Havemeyer, Loomis (January 1961). Yale's Extracurricular & Social Organizations, 1780-1960 (PDF). New Haven: Yale University. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/304683561.pdf

“Hillhouse Avenue.” The New Haven Preservation Trust, http://nhpt.org/hillhouse-avenue#:~:text=James%20Hillhouse%20established%20the%20genteel,which%20today%20bears%20his%20name.

Larry Milstein “Warner House Sees Shake-Up.” Yale Daily News, 2 Sept. 2015, https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2015/09/02/warner-house-sees-shake-up/.

Pinnell, Patrick. “Cloister Hall and Kirkland Hall.” The Campus Guide: Yale University, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 1999, pp. 142–144.

Scully, Vincent, et al. Yale in New Haven: Architecture & Urbanism. Yale University, 2004.

Strahan, Derek, Yale University, Yale University Archives, August 16, 2019 https://lostnewengland.com/tag/yale-university/page/2/

"Yale University" Newspapers.com, Boston Evening Transcript, August 8, 1900, https://www.newspapers.com/article/boston-evening-transcript-yale-universit/127766459/