Echos of Eternity: The Tempietto and the Enduring Architectural Legacy of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire // Yale University

The Roman Empire, a colossus straddling the realms of myth and history, left behind a legacy carved in stone that continues to echo through the ages. Its architectural marvels, from the sacred hearth of the ancient Temple of Vesta to the harmonious proportions of Bramante’s Tempietto, have laid the very foundations upon which Western civilization has built its cities. This essay will embark on a chronological odyssey, tracing the lines of Roman influence that stretch beyond the annals of history and into the heart of contemporary aesthetics and structural design. The uncovered relevance of Roman architecture, not merely as relics of an era but as vibrant blueprints that continue to shape our modern world, aim to illuminate how the architectural principles of an empire that once ruled the known world still govern the way society conceives and constructs living spaces centuries later.

ANCIENT ROOTS: TEMPLE OF VESTA AT TIVOLI

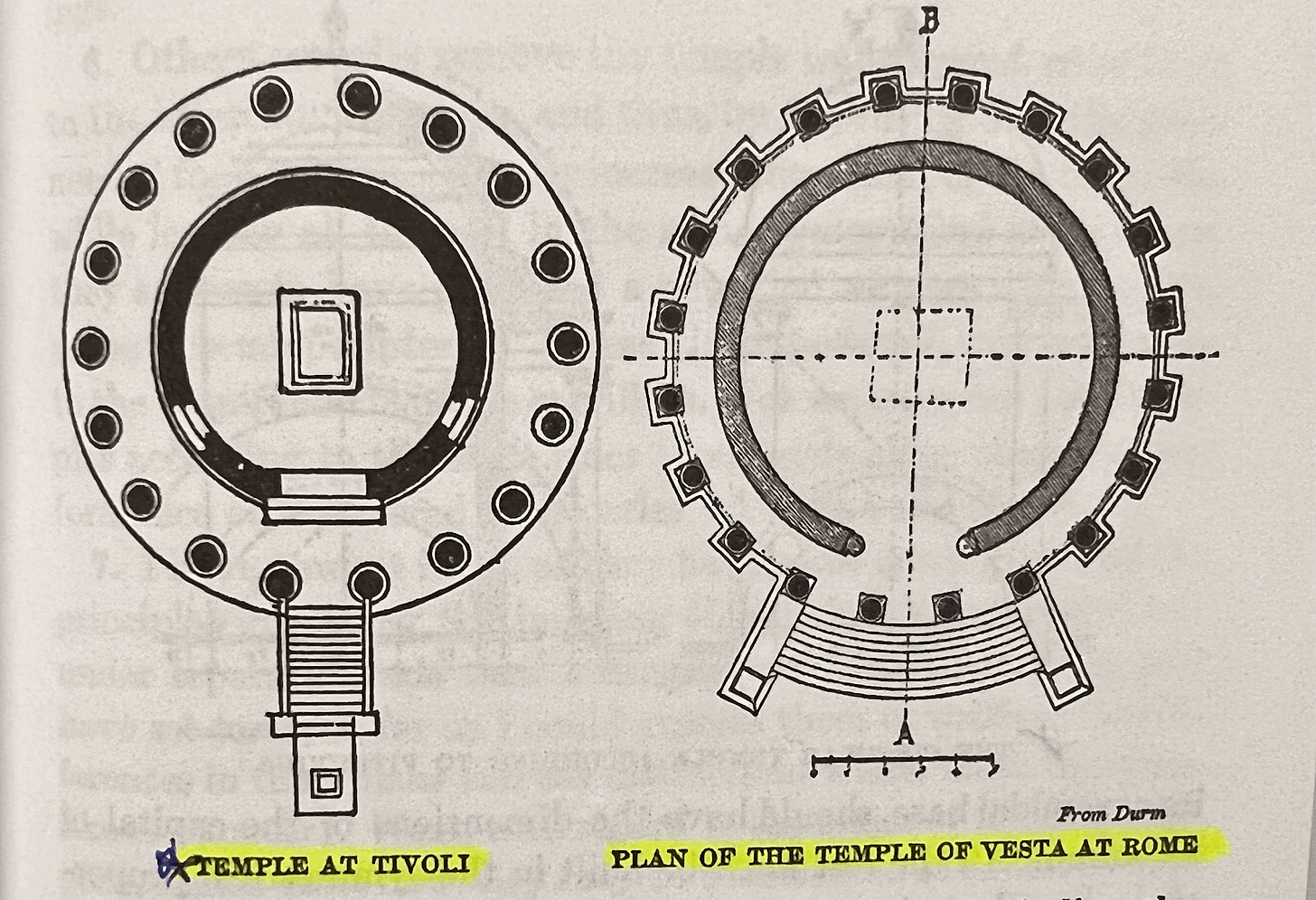

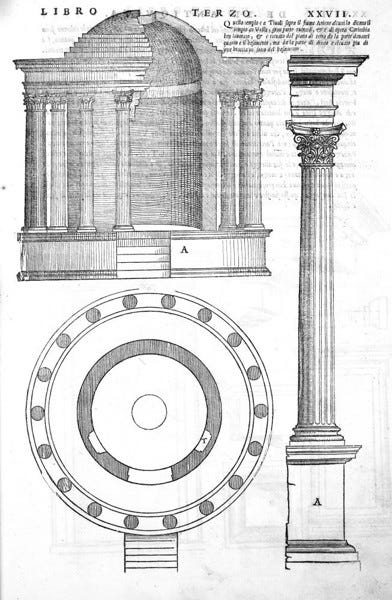

Nestled in the verdant landscape of Tivoli, the Temple of Vesta stands as a testament to the ingenuity of ancient Roman architecture. Dating back to the first century BC, this temple is celebrated for its distinctive circular form (Figure 1 and 2) —a departure from the conventional rectilinear temples of the time. This architectural choice was not merely aesthetic but symbolic, mirroring the round hearths of early Roman dwellings and paying tribute to the domestic hearth that were the heartbeat of Roman family and religious life.

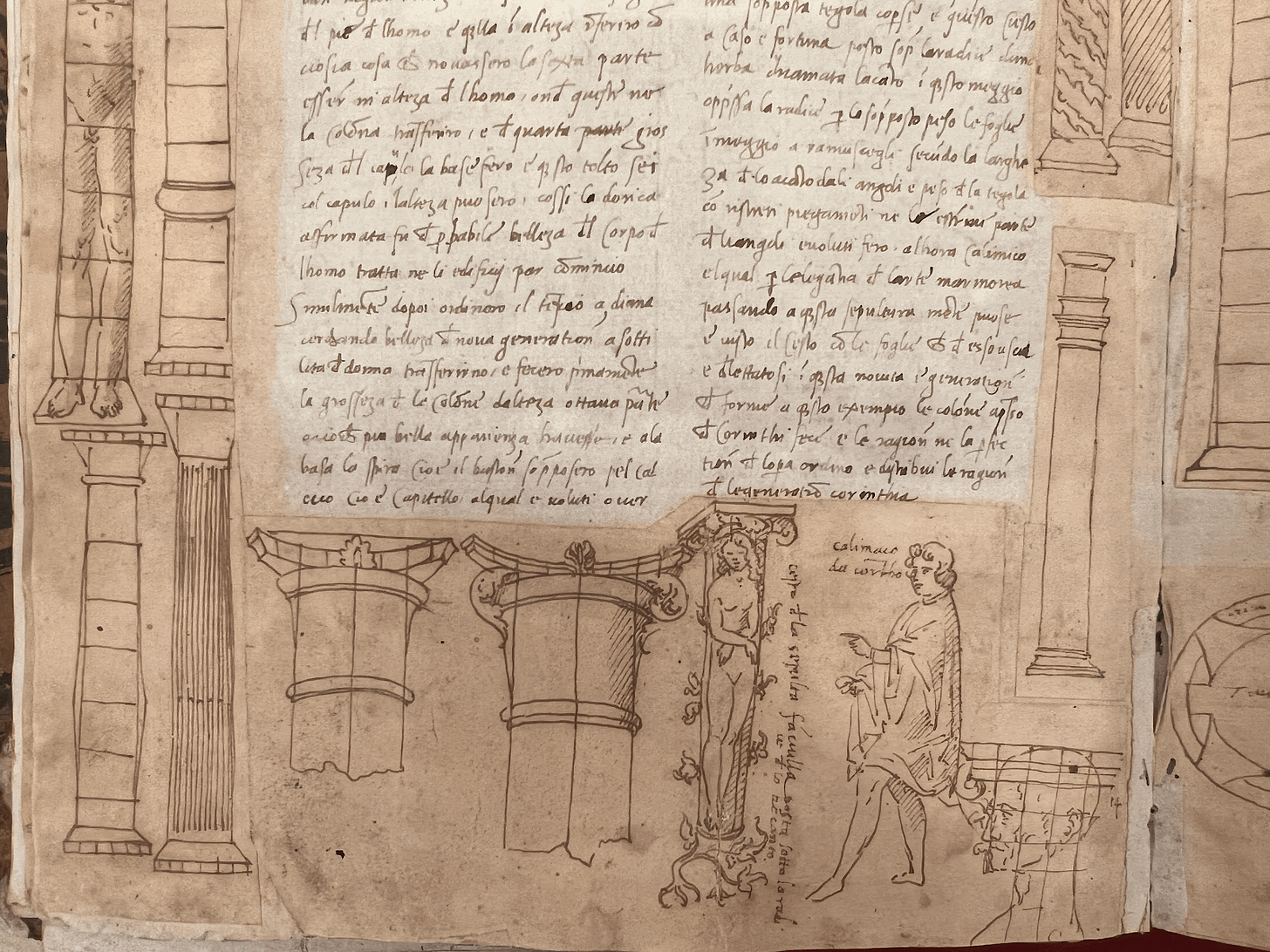

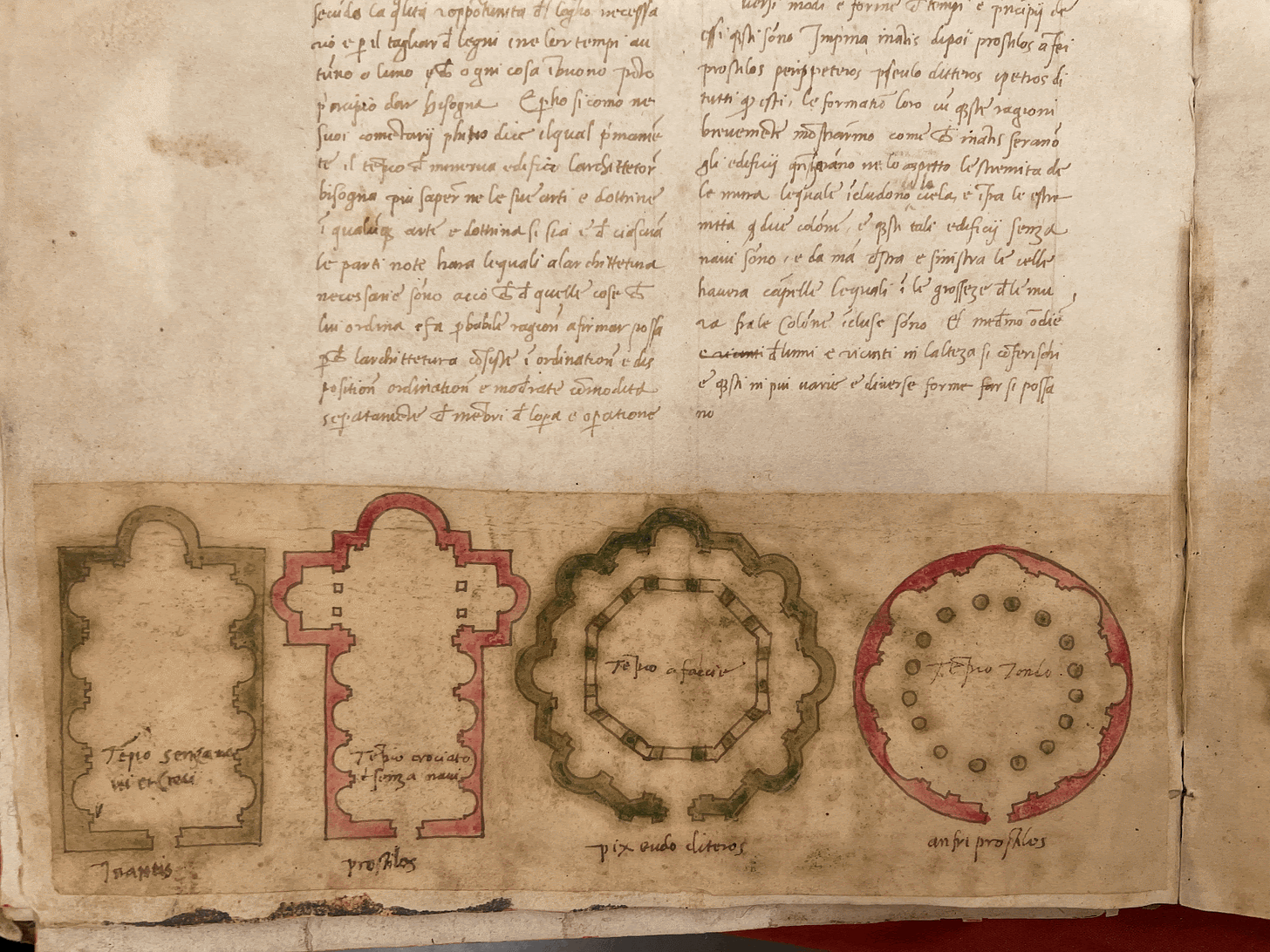

The temple’s distinctive Corinthian capitals, renowned for their intricate beauty, have inspired countless imitations, embodying the ancient notion that architectural forms should echo the nature of the human form. This concept captivated the minds of Renaissance luminaries, evident in Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic Vitruvian Man (Figure 3); da Vinci created this iconic illustration based off the standards and proportions set by Vitruvius, a military engineer, architect, and theoretician under Caesar Augustus. The Temple of Vesta is not only instinct in its circularity but also in the way the Corinthian design presents an exploration of form coming from the “slenderness of women” to reflect the delicate nature of maidens devoted to the goddess. It reflects the grace and delicacy seen in the slender elegance of maidens, as illuminated in manuscripts of Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Figure 4).

At the core of the temple’s design lay the sacred fire, a beacon of divine presence, ensconced within the temple’s central cella and vented skyward through an open roof (Figure 5). The fire within the temple was not just a literal flame; it was a symbol of the safety and prosperity for the Romans. If the flame ever went out, it was considered an omen of disaster for the city. Thus, the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli emerges not only as an architectural marvel but also as a profound emblem of the intertwining of the sacred and the civic, a perpetual reminder of the eternal flame that is the legacy of Roman architectural and cultural heritage.

THE TEMPIETTO: CEMENTING ROMAN LEGACY

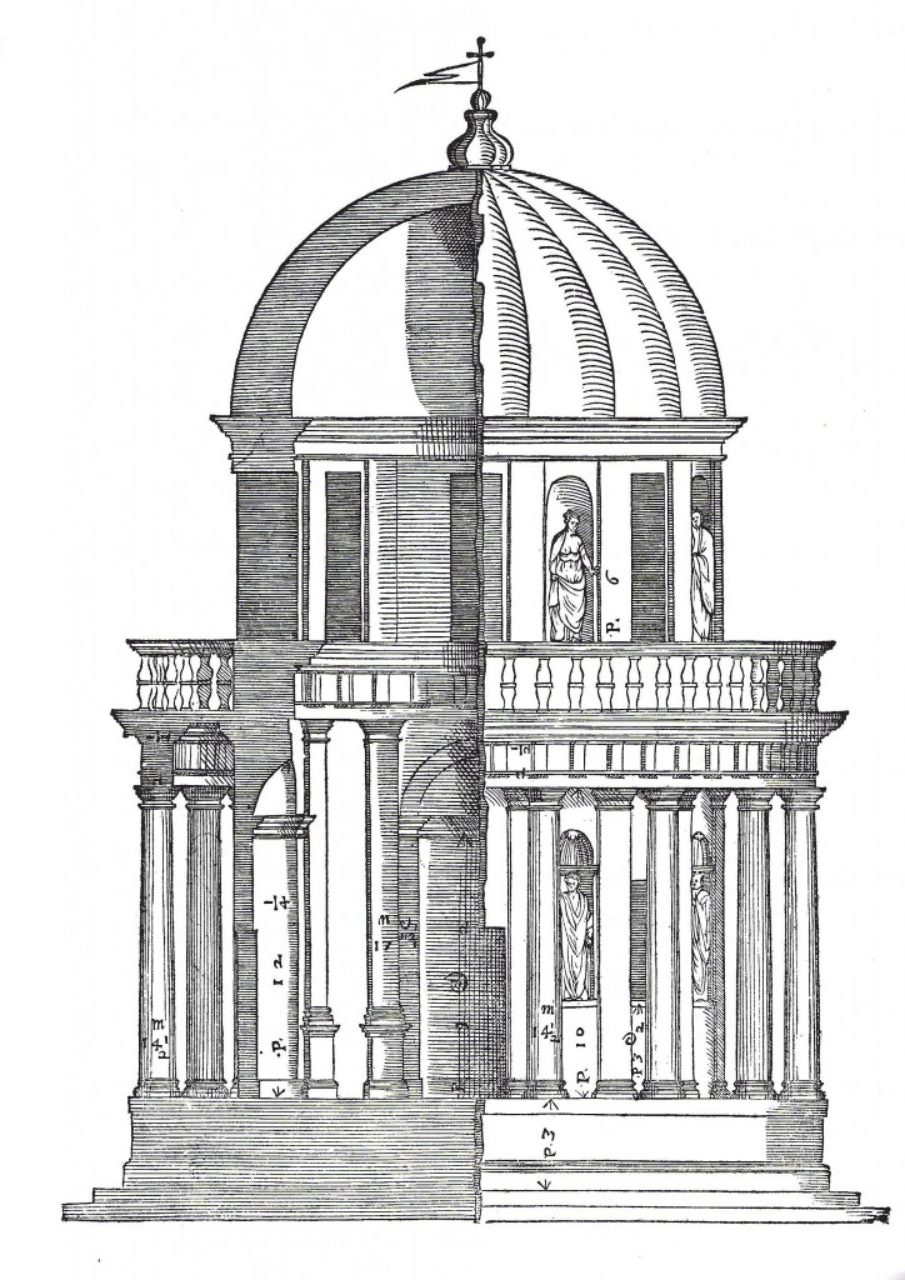

Donato Bramante’s Tempietto, built in 1502, stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Roman architectural principles (Figure 6). It draws inspiration from Vitruvius’s seminal work, The Ten Books on Architecture, which presents the most expansive and important documentation of Ancient Roman architecture. The Tempietto is a harmonious blend of ancient guidelines for monumental buildings and the creative spirit of the Renaissance. Its design is a homage to classical order, featuring a circular plan composed of two concentric cylinders—the inner one crowned with a dome—resting upon a rusticated base (Figure 7). This composition reflects Bramante’s reverence for the core tenets of ancient Roman architecture as elucidated by Vitruvius.

Not only does he dictate the correct proportions of columnade structure for various types of buildings in the empire, but he also cements the decision to use the Doric order since it was the “first [of the three orders] to arise.” Considered the earliest and most robust of the classical orders, the Tempietto utilizes this in an effort to connect the structure to the birth of architectural elegance. The Doric column, with its proportions derived from the human form through the “measur[ement of] a man's foot and compared this with his height,” thus embodied “the proportions, strength, and beauty of a man.” Although the Tempietto’s design is reminiscent of the Temple of Vesta, its dedication to Saint Peter—a male figure—aligns with the classical parameters of strength and masculinity. Bramante does maintain a nod to the status quo of the round temple, however, in his original inclusion of female figures in the carved entablature and between the colonnade (Figure 8). (These however will not come into fruition once the temple is actually built, as explained in the next section of the paper)

The Renaissance marked a profound rebirth of Classical culture, originating in Italy in the early 15th century and spreading throughout Europe. This period saw a resurgence of ancient Roman forms, including columns, round arches, tunnel vaults, and domes. Architects of the Renaissance, inspired by the ruins of Greco-Roman buildings and ancient texts, sought to revive the grandeur of antiquity. As such, the Tempietto’s design was inspired by classical temples, particularly the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, yet also expanded on these principles to reveal humanist ideals as well as have a greater connection to the catholic, rather than pagan, religion.

As a radial edifice, the Tempietto adheres to Vitruvian principles, evolving from a foundational round structure to a refined embodiment adorned with Doric columns. The building itself can be read from the outside in, beginning with three steps that lead to a peristyle of granite Doric columns encircling the central cella (Figure 9). Above the columns rises a distinctive entablature, composed of alternating triglyphs and metopes which is the first time this was seen in the Renaissance. It is also adorned with a decorative frieze and balustrade, culminating in a hemispherical dome perched upon a two-tiered drum. Despite its modest dimensions, the Tempietto’s adherence to classical proportions and its embodiment of divine harmony stand as a monumental achievement, a testament to Bramante’s mastery and the timeless allure of Roman architecture.

The dome of the Tempietto is one of its most striking features. It is composed of two concentric shells, and rests on a drum decorated with sixteen pilasters and sixteen windows — a deliberate nod to the Roman preoccupation with symmetry and the perfect number for form. This design choice echoes the ancient debate, as recounted by Vitruvius, between those ancients who favored the number ten, mirroring the human fingers, and mathematicians who argued for six, “because this number is composed of integral parts which are suited numerically to their method of reckoning.” Bramante, in a stroke of Renaissance genius, reconciles this conundrum by embracing the sum of these ideal numbers, thus achieving a proportional harmony that is both classical and innovative. In addition, sixteen columns encircle the core, supporting an entablature with a plain architrave, a frieze and a cornice detailed with dentils, creating a balance that is as masterful as it is sublime.

The location of the Tempietto, adjacent to the cloister of San Pietro, is no less significant in its design. Perched atop the Janiculum Hill, it offers a sweeping view of Rome, much like the grand vistas that were favored by the emperors of Rome for their monumental building programs. These programs were not just about building impressive structures; they were about integrating these structures into the fabric of the city in a way that would enhance the experience of the space and assert the presence and power of the emperor. In this sense, the Tempietto can be seen as a continuation of this tradition, engaging with its environment in a way that is both thoughtful and impactful. The panoramic view of Rome places the Tempietto in dialogue with the city, allowing it to be seen and experienced within the broader context of Rome’s topography and its historical layers of architecture. This thoughtful integration of architecture with its environment is a hallmark of Roman design philosophy, reflecting a deep understanding of how buildings can shape and be shaped by their surroundings. The Tempietto, though small in scale, is monumental in its program, echoing the ambitions of ancient Roman emperors to leave a lasting mark on the cityscape and to create spaces that would endure through the ages. In adhering to Vitruvian principles, Bramante ensures the Tempietto’s stature as a true monument, one that has served as a prototype for the monumental domes that followed, cementing its place in architectural history.

A CHRISTIAN TURN TO TEMPLES

A jewel of Renaissance architecture, the Tempietto stands as a profound symbol of the Christian faith and its rich history. Commissioned by the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, this “little temple” marks the hallowed ground where, according to tradition, Saint Peter suffered martyrdom at the hands of Emperor Nero. Transcending its role as an architectural feat, the Tempietto bridges the spiritual and the temporal, connecting the ancient grandeur of Rome with the sacred narratives of Jerusalem. The Tempietto is not only a beautiful monument, but also a symbol of the history and faith of Christianity. It represents the connection between Rome and Jerusalem, between the ancient and the modern world, between paganism and Christianity. Its sacred and historical context captures the essence of the Renaissance ethos, showcasing the often blended artistic innovation with the profound themes of spirituality and history.

The Tempietto is a wholly sacred building, marking the traditional site of St. Peter’s crucifixion and in essence acting as an architectural reliquary. It looks back to the tradition of an early Christian building called a martyria, which was a marker of the site associated with an early Christian martyr, yet is also a reinterpretation of ancient temples. By being a contemporary religious interpretation of pagan religious structures, it is effectively using the forms’ connotation to give a testament to the enduring nature of society, culture, and traditions. For instance, the female maidens of Bramante’s original design had been altered to instead become a symbol of the monolithic religion the temple has been altered to. Here, between the triglyphs of the Roman Renaissance, the frieze “bears insignia of the papacy in the metopes.” As keys are a symbol of Saint Peter, who was the first pope, and his successors, this is an “explicitly papal” decision that is meant to diffuse a “liturgical significance” to the whole of the building program.

Additionally, the ‘altar’ at the heart of the Tempietto, marking the precise location of Saint Peter’s crucifixion, is a vestige of pagan worship within classical architecture as both are done at the center of the round temple’s cella, exemplifying how Christianity has adapted and integrated these ancient forms. By borrowing both from that early Christian tradition and directly from Antiquity, the Tempietto acts as a direct link between 16th-century Rome and ancient Rome.

The Tempietto intends to create a sacred place, emphasizing the pious nature found at the root of Catholicism in its simplicity. Its use of concentric circles can thus be interpreted as a concentration or even a hyperfixation on a particular point, similarly to the way a temple for the Roman gods would. It then comes inwards with each layer to allow for one’s focus and ensure meditation from the outside world. Beneath the Tempietto lies a marble pattern that converges on a central point, encircled by additional concentric circles that frame an emerald stone (Figure 10).

This stone marks the crucifixion site of Saint Peter, accentuated by its hue and the surrounding design, allowing the devout to gaze upon it from above, reinforcing its sanctity and significance. The circular design, a motif of profound spiritual significance, embodies the concept of infinity as it has no beginning and no end, symbolizing perfection and eternal nature. The grandeur of Roman Amphitheaters, the majestic dome of the Pantheon, and even the Colosseum (Figure 11) are all testaments to this geometric reference. Moreover, the circular form is not merely an aesthetic choice but also a recurring theme in the designs of public buildings and sacred spaces, constantly rediscovered and altered by architects (as indicated in Figure 12). In due course, the Tempietto’s depiction also solidified its place in the canon of classical antiquity through Martini’s Treatises (Figure 13), underscoring its indelible impact on the Roman ethos. The Tempietto, more than a mere structure, emerged as a symbol of the Roman world’s architectural legacy that continues to inspire, bridging the past with the present, and exemplifying the timeless influence of Roman artistry and thought.

LASTING IMPORTANCE OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The Tempietto, a crowning achievement of Renaissance architecture, stands not merely as a revival of Vitruvius’s classical round temple but as an indicator of a new era of Roman architecture. It served as a “prototype for the burgeoning Golden Age” that was being heralded by the orators of papal Rome. This architectural masterpiece forges a connection between the “rustic Tuscan order” and the papacy, showcasing a harmonious blend of Tuscan columns, a Doric entablature, and a rusticated base. These elements, prefigured in Bramante’s Tempietto, create a visual symphony that resonates with the grandeur of Rome’s imperial past and the spiritual authority of the papacy, cementing the Tempietto’s place as a pivotal link in the next reincarnation of the Roman architectural tradition.

Just as the Temple of Vesta served as an inspiration to the Tempietto, the latter has inspired many buildings of modern importance, such as the Rotunda at Yale’s Schwarzman Center (Figure 14). The domed circular portico provides an entrance link between Yale University’s Commons and Woolsey Hall, hinging the two long halls which splay from the portico at a nearly right angle. Though it may have a different function, its physical similarity through its dome, two concentric cylinders, and columns (though here they are of a Corinthian order) furthers the classical elements of the Vitruvian temple. It remains a place of gathering, with a central cella that is now used for important devotions of a different nature, such as student conversations and protests, proving that function can follow form, even if it is to a certain degree

CONCLUSION

The Tempietto, a powerful beacon of Renaissance architecture, has cast a long shadow over the annals of architectural history. Its influence permeates the design of monumental domes and grand edifices that have risen since its inception. This architectural gem, conceived by Bramante, encapsulates the quintessence of Roman architectural traditions—symmetry, proportion, and the classical vocabulary. It not only mirrors the aesthetic ideals of the Romans, which celebrate architectural beauty in resonance with human scale, but also marks the highest point of the Renaissance’s homage to Roman ingenuity. The Tempietto served as a precedent that has guided architects through the High Renaissance to the Baroque period and beyond, its principles resonating in contemporary structures, such as Yale’s Schwarzman Center, which reinterprets the ancient circular temple’s function to meet the demands of its urban milieu.

In this way, the Tempietto stands not only as a testament to the past but also as a living dialogue with the present, continually inspiring the reimagining of space in accordance with the timeless ideals of Roman architecture. Its legacy is a testament to the lasting importance of Roman architectural traditions, proving that the principles established millennia ago still hold relevance in shaping the spaces of today and tomorrow.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Cattermole, Paul. "The Tempietto." In Architectural Excellence: 500 Iconic Buildings, https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6Mzk1MTcwMA==?cid=1032

Darius Arya, The American Institute for Roman Culture, “Vesta, Forum (Temple of Vesta)” Ancient Rome Live. March 26, 2021. https://ancientromelive.org/vesta-forum-temple-of-vesta/

Department of European Paintings. “Architecture in Renaissance Italy.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, (October 2002) http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/itar/hd_itar.htm

Freiberg, Jack. “Bramante’s Christian Temple.” In Bramante's Tempietto, the Roman Renaissance, and the Spanish Crown, 63–101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107337664.005.

Freiberg, Jack. “Temple, Tabernacle, and Sepulchre: The Legacy of Bramante’s Tempietto” Sacred Architecture Journal, Volume 39, 2021 https://www.sacredarchitecture.org/articles/temple_tabernacle_and_sepulchre_the_legacy_of_bramantes_tempietto

Loth, Calder, “The Corinthian of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli.” Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, October 30, 2013 https://www.classicist.org/articles/classical-comments-the-corinthian-of-the-temple-of-vesta-at-tivoli/.

Loth, Calder. “The Tempietto, Grandfather of Domes.” Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, 2012, https://www.classicist.org/articles/classical-comments-the-tempietto-grandfather-of-domes/#_edn3.

Martini, Francesco di Giorgio. Treatises on Architecture, Engineering and Military Art, 1482. Beinecke MS 491. New Haven: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Rowland, Ingrid. “Bramante’s Hetruscan Tempietto.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 51/52 (2006): 225–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25609495.

Vitruvius. Ten Books on Architecture. Translated by Morris Hicky Morgan. New York: Dover Publications, 1960.