Articulating Aesthetics: The Semiotic Symphony of Visual Language

Critical Approaches to Art History // Yale University

The semiotic strategies employed by art historians Iversen, Bryson, and Krauss serve as a decoding lens for the tapestry of visual art. Their relevance to current art historical analysis and limitations are made clear considering Wang’s study of woven writing in early China, which uses a thorough analysis of materiality and process to inform an interdisciplinary view of the signification and transformation of writing in different media and contexts.

One similarity between Iversen, Bryson, and Krauss is that they all draw on the linguistic theories of Saussure to understand the signifying systems of visual art. Iversen argues that Saussure’s model of the sign, composed of the signifier and the signified, can be applied to the analysis of paintings, sculptures, and photographs, as they are also forms of communication that convey meaning through arbitrary signs known to particular audiences. A reliance on Saussure’s linguistics as an example for semiotics in art is questionable from the start, as despite its aid in explaining the concept and its uses, Iversen points out its shortcomings primarily in the way that art is supposed to transcend the boundaries set by languages, and in doing so, needs to be looked at in relation to other communicated ideals and motifs. A single study alone cannot be extensive and exclusive enough, no matter the efficiency in which the root of a word can be found and inform its current use. Bryson extends this idea and proposes that the distinction between discourse and figure, or the verbal and the visual, can be understood as an opposition between the symbolic and the iconic modes of representation.

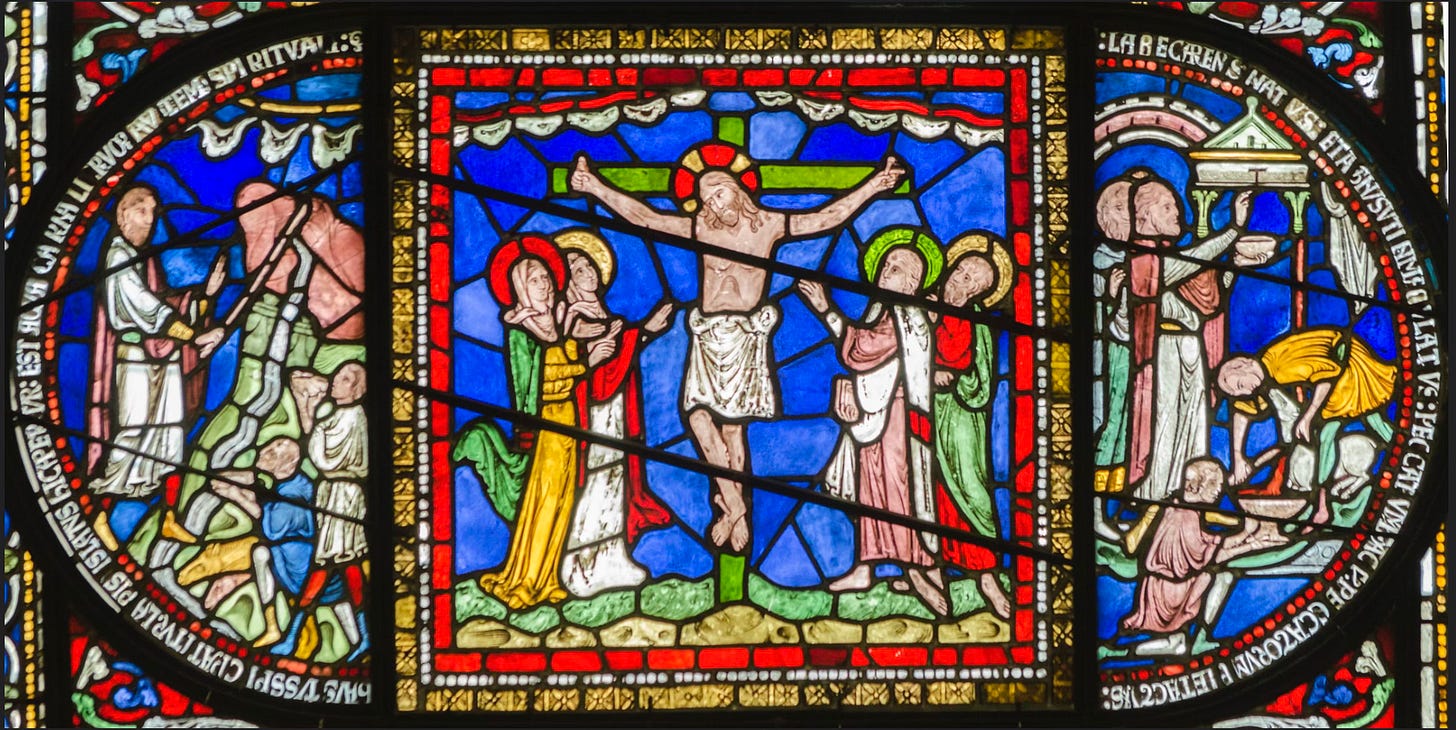

Here, however, Bryson interjects and states that this extreme juxtaposition and traditional approaches to contextualization in art is all relative, going as far as to say that “only those visual effects we currently agree to call realistic” can be considered as natural to all viewers (Bryson, pg. 8). The author’s case study of the stained glass windows at the Canterbury Cathedral and the Masaccio painting in comparison to the Essential Copy stress of the “hierarchy of semantic relevance” which contrasts Saussure’s proposal, questioning whether it is still useful for the art historical practice today (Bryson, pg. 9).

Krauss also adopts Saussure’s concept of the sign but criticizes the notion of originality and authenticity in modernist art, specifically collage. She argues that the avant-garde artists such as Picasso were not creating new forms of expression, but rather reusing and transforming existing cultural signs; in doing so, they took the signs out of their original context (one that Saussure implied shouldn’t be taken into consideration) and gave it a new one through proximity and changed meaning.

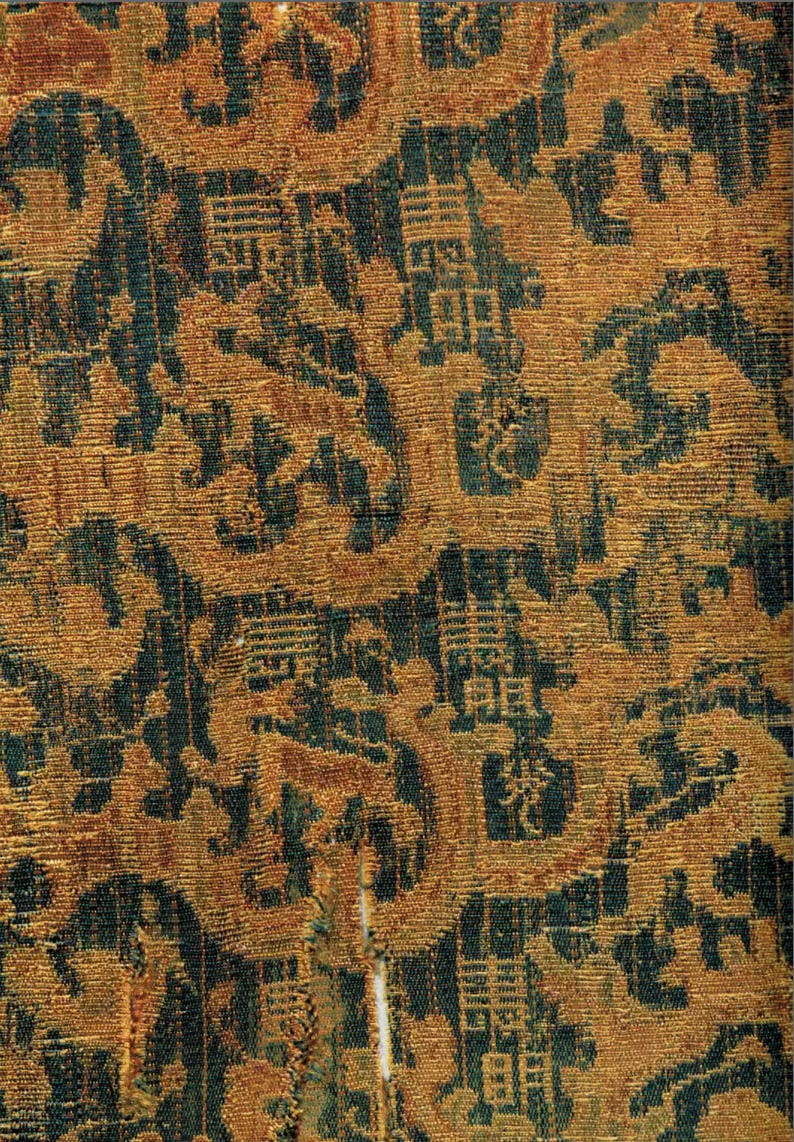

A more recent reading, Wang’s study of woven writing provides an interesting caveat to this conversation as it deals with the Chinese script and its translation in a weaving medium to become art. Its actual linguistic meaning was challenged, yet interestingly “weavers became both makers and readers of writing” when taking into consideration the textile’s warp and weft threads, color schemes, etc. The symbols become patterns, and this interdisciplinary view of the matter allows one to see the complexity of the signifying processes involved in the production and reception of woven writing, as well as the historical and cultural factors that shaped them.

While these authors share some common assumptions and methods based on Saussure’s linguistic theory, they also differ in their focus, scope, and conclusions. Moreover, Wang’s study of woven writing challenges some of the premises and categories of the semiotic approaches, and offers a different perspective on the relationship between language and art, as well as the role of materiality and temporality in signification. This reveals the complexity of the semiotic theories and practices in art history, with further discussions needed to establish the possibilities and limitations of applying linguistic models to visual analysis.

Sources:

Margaret Iversen, “Saussure vs Pierce: Models for a Semiotics of Visual Art,” The New Art History (1986), 82-94.

Norman Bryson, “Discourse, Figure” inWord and Image: French Painting of the Ancien Régime(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 1-28.

Rosalind Krauss, “In the Name of Picasso,” The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths(Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1985), 23-40.

Michelle H. Wang, “Woven Writing in Early China,” Art History, Vol. 42, no 5 (November 2019): 836–61